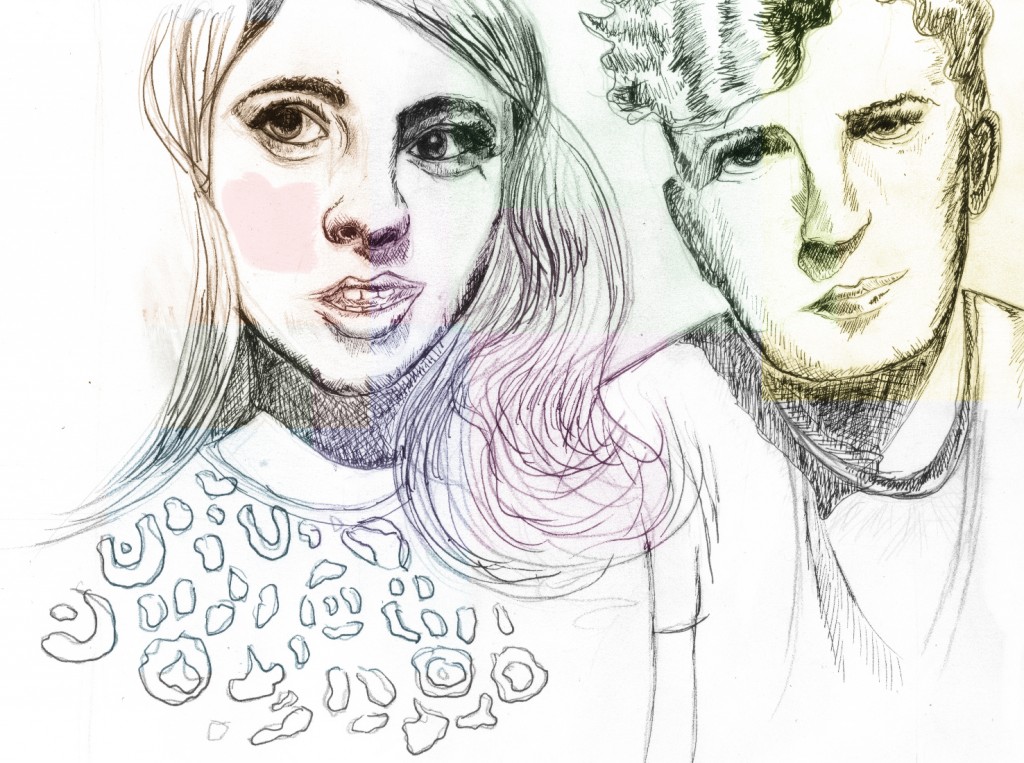

Alex is short and funny. She laughs and whirls, cracks wise on tangents, then smiles a big flashing, mile-long grin to bring it back home. She goes to shows, teaches young girls to play the bass, jokes and giggles and wants to bring about real reform in immigration policy.

Ed is tall and also very funny. It takes a while for his funny to come out. It’s dry, witty. His deep voice sounds serious even when he’s not. It takes on an urgency when he’s talking about music, writing, music, cinema, music. Anything he loves, he stresses the words. He wants you to feel what he feels.

Together, Alex Fryer and Ed McMenamin are the team behind Dumpster Tapes, a cassette label of punk, garage and other DIY bands. They want you to listen to their music.

To get it out of the way, yes. Cassettes. Like little plastic square, dub top 40 hits off Casey Kasem, stick a pencil in one of the holes to untangle the thin, magnetic tape after your sister’s boombox started chewing up the “Use Your Illusion II” your mom let you buy at Sam Goody’s. Those cassettes.

“For people that go to a lot of local garage or punk shows, it makes sense because they already see cassettes on merch tables and buy cassettes.” McMenamin said. “When I tell my parents or cousins or something, you explain it and they kind of get it. You give them the practical reasons for it: the economics of it being affordable and that people have the nostalgia or the novelty memory of cassettes.”

No one buys CDs anymore, you can’t slip a record into your pocket at a show and, although each Dumpster Tapes tape includes a link where the buyer can download the music, online doesn’t offer any physical presence. There’s nothing to hold and touch for band or producer to say “I made this.”

They’ve put out music by local acts Son of a Gun, Gross Pointe, Pinebocks and Flesh Panthers and German-based Sick Hyenas.

McMenamin, 28, is a reporter for a suburban newspaper chain. A Springfield native, he moved to Chicago almost three years ago for work and for music. He has done some music writing, but never wanted to be a music journalist.

“Sometimes it’s more fun to just be enthusiastic and promote the stuff you like rather than having to be ‘I like this album, but now I have to overintellectualize it for 500 words,’” he said.

Fryer, 22, is a Hyde Park native. At Bryn Mawr, she helped run a concert series, but couldn’t generate any interest in starting a college label.

“None of the other girls really got behind it,” Fryer said. “It was disappointing.”

Back in Chicago, she DJ’ed for WHPK and taught at Girls Rock, but wanted to get more involved in the music scene.

The two met at a show (naturally) and started talking music. Dumpster Tapes was underway.

The name came from a desire for the gritty, grimy, DIY attitude. The logo came from illustrations a friend did for a zine Fryer planned to do about the Pitchfork music fest.

“She had done these two doodles of a little slime monster — because it was really rainy that weekend — singing into a microphone and playing the guitar,” Fryer said. “And I was like, if we could use something similar to him, put him in a trash can, have him holding a cassette, make him even grimier, I think that would be perfect.”

Then, the why. Why put out music rather than just listen to it? Why promote bands rather than just like them? Why tapes, why slime monsters, why any of this?

“Maybe it’s that I’m vain and think I have good taste,” Fryer said, laughing among the jukebox tunes and clack of pool balls at the Wicker Park bar where we agreed to meet. “I like the kind of stuff I think other people would like.”

“It’s almost like an extension of that,” McMenamin added. “You get excited about music and you want-”

Here, Fryer chimed back in. Here, she added her lilting, twirling, laughing alto to McMenamin’s rich, deep and misleadingly serious-sounding baritone. By mistake or rapport, they completed the sentence together in what seemed to me a perfect Dumpster Tapes mission statement, should they be looking for one.

“To share it with other people,” said Ed and Alex.