I recently heard a political guy fulminate against tax increment financing — one of the hot-button issues of the upcoming election and a funding source either raising or stealing billions of dollars, depending on who you ask. He inspired me.

He inspired me to take a couple of these 1,001 afternoons to explain TIFs, because that guy clearly didn’t know what he was talking about.

On Wednesday, I touched the broad strokes — why we have TIFs, what they do and why they’re only as bad as the person using them. Today, we’re getting into the nitty-gritty.

How TIFs work

How taxes work

How TIFs work

Back to Faketown

Back to reality

Taking a step back

Wait, what?

What can be done

How TIFs work

Wait, let’s not get into this yet.

How taxes work

Better.

If you’re really interested how Cook County figures out what your home is worth, I did a fun, silly video a couple years ago explaining property tax assessment. It’s incisive, hilarious interactive journalism. (Hire me, Curious City.)

All you really need to know for this is that one of the numbers they use to figure out your tax bill is called the EAV. It stands for “equalized assessed value” and it’s the amount of your home’s value that they can tax.

In every Illinois county but Cook (because players gotta play and Chicago’s gotta do needlessly complicated and somewhat suspicious things with money), a property’s EAV is 1/3 of its market value. Add up all the property EAVs in an area, you’ve got that area’s EAV. It’s sometimes called the tax base.

Faketown, Ill., (which I’m putting in Fake County rather than Cook to keep the math simple) isn’t sure how to save East Faketown, the poor, depressed and blighted side of town where the property market values are stagnant or declining. East Faketown’s EAV, being 1/3 of crap, is crap.

Tax time comes and the schools, parks, city, county, East Faketown Mosquito Abatement District and other governments ask for their chunk of the EAV. This is called levying.

It goes like this:

Levy / EAV = Tax Rate

So if the EAV stays the same — like it does in a blighted area — and all the schools, parks, etc., are asking for more money because their costs went up — as costs do — then either your tax rate goes up or the governments can’t get the money they need.

The purpose of a TIF district is to bring up that EAV. Its purpose, written into state law, is “to enhance the tax bases of the taxing districts.”

How TIFs work

Let’s say Faketown wants to help John’s Steel Mill set up shop on some vacant property in East Faketown.

It’s a good project. Faketown will be able to start collecting property taxes off the land once the mill is up and milling, plus there will be new jobs, so people will fix up their houses, other new businesses will come in, etc. Planners expect the EAV to grow like wow from this.

Faketown has to give the steel mill a good deal, or else John will set up shop in nearby Exampleville.

I should mention here all this is ridiculous. A modern TIF in Chicago is not luring manufacturing jobs. Historically, it’s been a fund for whatever the mayor wants, from Daley saving a historic building from a development he didn’t like to Emanuel trying to increase property taxes revenues by buying tax-free land for a hotel.

Faketown is, however, more what the state TIF law was designed for back in 1977. There were some reforms added in 1999, but in general we’re dealing with loose definitions, loose rules and almost no ability to stop a mayor who decides to use the money any which way but Faketown.

But I digress.

Back to Faketown

A city or town raises that money for John’s Steel Mill by setting up some boundaries and locking the EAV used to calculate the governments’ share of that area’s tax bill for 23 years.

During those 23 years, all these improvements are going on that are increasing the EAV. The tax bills are collected based on the new, better property values, but the amount given to the schools, parks, cities, counties and mosquito abatement districts is calculated based on the old, craptacular property values.

Makes sense, right? Without John’s Steel Mill and all the growth it created, the East Faketown EAV would still be craptacular. The school districts and stuff are just getting what they would have gotten anyway.

It’s called the “but for” rule. A TIF district can only touch money based on growth that wouldn’t have happened “but for” the TIF.

Once the 23-year life of a TIF is done, any money left in the fund goes back to the schools, parks, county, etc., that would have gotten the money if not for the TIF.

Or would, if this were not Chicago

Back to reality

The ideal is you’ll start a TIF, go to a bank or other financial institution and say, “Hey, we don’t have any money for this project, but if you take a look at our numbers, once the project is done we’ll have all this money in the TIF fund to pay you back. Now how about some bonds?”

In short, you’re borrowing against future growth you predict will occur after the project is in place. A 2009 paper by Cook County Assessor’s Office staffers calls this a “classic TIF district.”

Then there’s the other type of TIF, which the report says work on “a pay-as-you-go basis.” That’s when they take money debt-free from the fund as it comes in.

And that’s ridiculous.

If a TIF fund is growing on its own, the area’s clearly not blighted. Why is there a TIF district there? Why is it allowed to touch money that would have been raised there whether or not the TIF existed?

Worse, the less the EAV growth is due to the TIF district, the bigger the costs to the taxpayers and schools.

According to the 2009 paper, if:

TIF caused all of the growth: No cost to the governments and tax bills stay the same

TIF caused some of the growth: No cost to the governments, but tax bills go up

TIF caused none of the growth: “To the extent that TIF districts were not responsible for the growth of new property within them, taxing agencies lose revenue over the course of the life of each TIF district.”

Taking a step back

OK, so if all the growth came from the TIF project, everything’s good. If all the growth was natural, the schools and parks and stuff are losing money. If it’s a mix, then the schools are fine, but the taxpayers are getting the shaft.

So how do you tell what caused what growth? Well, you sorta can’t.

There are clues a TIF is poaching natural growth, like if the city didn’t put any money in the TIF’s budget to repay loans.

“Seventy-five percent of all Chicago TIF districts have no funds reserved for debt service,” the 2009 report said. “This would suggest that these districts are utilizing revenues from naturally occurring growth in property values instead of borrowing to make initial investments in development within the district.”

Another clue is if the fund started growing before the project even started — like the $9.6 million raised in the first year of the LaSalle Central TIF district, or the $3.4 million raised in the first two years of the Wilson Yard TIF district. (Wilson Yard is in a gentrifying area, LaSalle Central is in the ritzy financial district downtown.)

Another clue is if the money had been moved out of the TIF district it was raised in, which is totally a legal thing a city can do.

Wait, what?

Despite all the talk about raising funds locally, the city can use money raised in a TIF district on projects outside of the district.

… as long as it’s moved into another TIF district

… and the TIF district it’s moved to is touching the first one

… because municipal financing is apparently that kid at tag who thinks grabbing onto the kid touching base makes him safe too.

In fairness, John’s Steel Mill will probably hire from West Faketown as well as East Faketown and a new “L” station in one neighborhood would help people one neighborhood over get to work too. Benefits cross lines.

Sometimes.

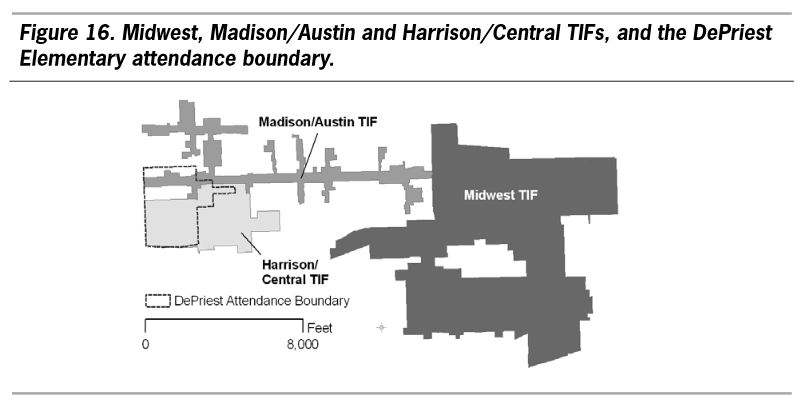

Here’s an example from a 2007 report distributed by U.S. Rep. Mike Quigley back when he was a Cook County commissioner:

The city was moving $18.5 million from the Midwest TIF (designed to help the North Lawndale and East Garfield Park communities) alllll the way down that thin (but adjacent) corridor to build DePriest Elementary School in South Austin.

None of the kids living in the Midwest TIF go to that school. South Austin needs help, but they did it with money supposed to help North Lawndale.

What can be done

If your college kid uses the “for emergencies only” credit card for pizza and beer, you don’t ban credit cards. You sit the kid down, explain exactly what you consider an emergency and tell the little brat what you’ll do if you get another bill for 2 a.m. Papa Johns.

Whether or not you or I personally agree with them, all these uses are legal, because the law gives municipalities so much freedom in creating and using TIFs.

Changing that means contacting your state legislators — you can find your representatives here — and tell them you want comprehensive TIF reform. It’s a long shot, but it beats no shot.

Luckily for us, analogies only work until a point. After that, you have to actually talk about what you’re talking about.

In this case, my (admittedly brilliant) college kid metaphor falls short. Parents can’t choose their kid, but we damn sure can choose the mayor and city council who will use TIFs in a way we, individually, find appropriate.

The April 7 runoff will pit Mayor Rahm Emanuel against Cook County Commissioner Chuy Garcia. There are also runoffs in 19 of the 50 wards. Look at their platforms, look at their plans and vote for the people you trust with this powerful, potentially dangerous tool.

Information on grace period voter registration can be found here.

Coming Monday: Back to beggars and birds and steelworkers and stuff for the other 999 Chicago Afternoons.