He’s building a slave ship in the basement.

He wants noises and lights outside the faux portholes to create the sensation of a sea at motion. He wants creaks of timber and he wants the wax replicas of chained slaves to feel like human skin to the touch. He wants a fog machine to perfume the air with a light reek of feces, urine, vomit and the other human rot that brought millions of Africans to America in chains.

It’s not just any ship Sam Smith wants to build in the basement of a restored Englewood mansion. It’s the Zong, which provided one of the most horrifying stories of one of the most horrifying eras of human history.

“What would happen was the slavers were running insurance scams,” Smith said. “A lot of major insurance companies were insuring the passage of the slaves across the Atlantic. What they were doing is they were dumping cargo just to file insurance claims.”

The cargo was people. The crew of the Zong poured 132 humans into the Atlantic, claiming in court water supplies were low and the other option would have been the agony of death by thirst. 54 women and children were dumped into the sea the first day, 42 men the second day, 36 other slaves over the days that followed.

The “death by thirst” claims were a lie. The Zong had 505 gallons of drinking water on board when it pulled into Jamaica, plus there had been a rainstorm of fresh, collectable water the day they dumped the men. After weighing the evidence, a British appellate court found the insurance company did not have to pay out the policies. The court battle about the Zong was, after all, a matter of insurance liability, not murder.

The Zong massacre of 1781 did give fodder to Europe’s abolitionists, who spent the next few decades citing the case to get the transatlantic slave trade, and later slavery itself, abolished country by country.

“Slavery didn’t end in Europe because of some humanitarian effort, but because of legal reasons and money,” Smith said.

And it’s going in his basement.

The Perry Mansion Cultural Center is beautiful. I don’t want readers still caught on the description of noise and slave-ship vomit to believe anything else. Englewood residents take their lunch breaks across the street to look at the bright summertime flowers in a yard that once grew only mud.

Smith is currently changing over the arts center to a new exhibit. Amid scaffolds and ladders in the bright, airy main floor, a hand-painted mural entwines the top of the walls. A thick ribbon of drywall curved as far as 80 degrees runs through the rooms. The chimney has been converted to a wooden statue, brand-new boards artificially aged to vintage through a process of Smith’s own devising.

But the purpose isn’t prettiness. The mural is of the history of America, the slavers’ markets and human-bound ships that carried Africans in chains. The ribbon of drywall will act as canvas for a series of pieces drawing attention to Mauritania, which still has an open slave trade despite its government’s claims any talk of human rights abuse is the work of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy. The chimney statue is a sweatbox, where slaves were locked crouched in the heat as punishment.

The second floor will be an exhibit on the Flint water crisis and other sections of the world where environmental injustices keep the poor from the resources they need.

Each temporary exhibit hits a different social issue to spark conversation, action, thought, change. The basement Zong, which Smith estimates is five years away from completion and whose development you can support by contributing to the Perry Mansion Cultural Center GoFundMe campaign, will be the only permanent piece among a rotation of social justice themed artwork on the floors above.

“There are 15 artists from all around the world that are part of the collective of this space, not including me,” Smith said. “I’m the 16th artist.”

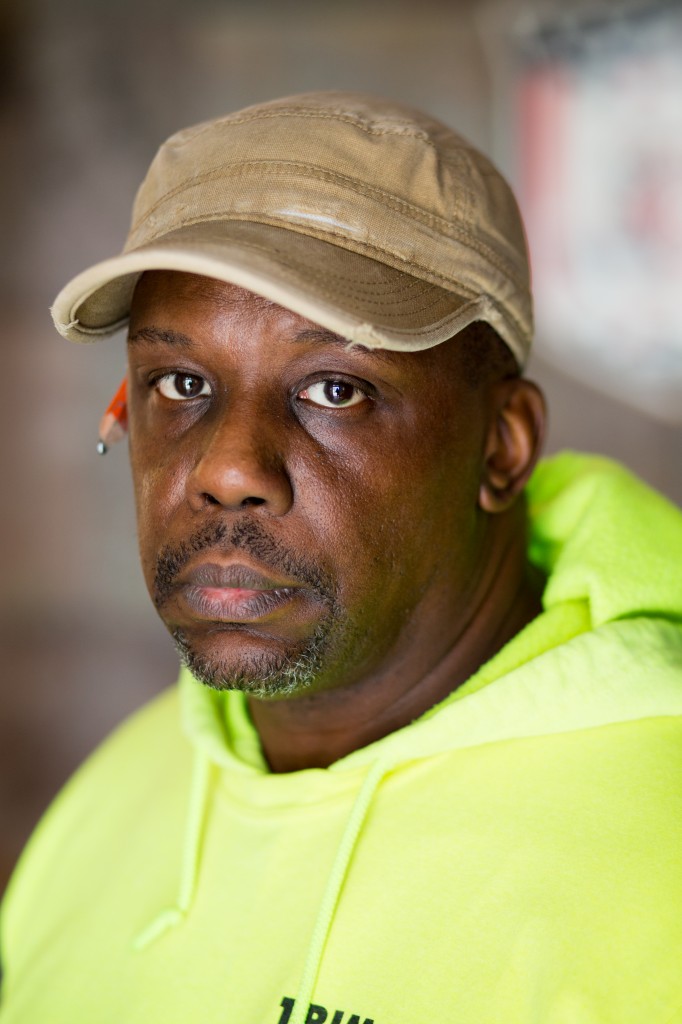

Sam Smith was born in Mississippi, but raised in the Henry Horner Homes projects on Chicago’s West Side. One of 15 children, he became his father’s informal assistant and apprentice early on. “My dad was a master carpenter and furniture maker, so I was always around the trades,” Smith said. “From the time that I was 5, I was his helper. So he made me go with him, taught me every trade except roofing and heating.”

Now a master carpenter himself, Smith, 47, has worked since age 11 when he made and sold greeting cards. He appeared in McDonald’s corporate training videos in high school. After college he started and ran a local newspaper, then a sports and entertainment magazine. Eventually, he landed on real estate development.

“I’m not doing it now but I was doing quite a few projects before the real estate market crashed,” the 16th artist said. “I would buy properties in middle class neighborhoods and impoverished neighborhoods all around the city, all around the country. And I really took pride in buying dilapidated properties and restoring them and making them breathtaking and then selling them at reasonable prices so people in those communities can have an opportunity to live in a really nice property at a price point they can afford.”

One of those sales took him to the house at 7042 S. Perry Ave. in Englewood.

A brief pause for some statistics.

The Englewood neighborhood running between West Garfield Boulevard to the north and West 76th Street at its southernmost comprises 3.07 square miles and 30,654 people.

Once an oak forest in Potawatomi land, the neighborhood saw its first non-native settlers among German and Irish “truck farmers” in the 1800s growing produce for the market. It stayed white. Once the U.S. Supreme Court made racially restrictive covenants — binding deeds promising a property would never be sold or rented to members of certain races and here’s a map of Chicago’s covenant areas in case you don’t believe this — illegal in 1948, residents of the “Black Belt” to the east started moving in.

Whites fled from their new neighbors. The neighborhood was 2 percent black in 1940 and 96 percent black by 1970. Processes such as redlining (denying loans and other financial services or charging higher interest rates in certain neighborhoods based on the racial makeup) ensured the black neighborhood was a poor black neighborhood.

Resources remain low today and drugs, violence and prostitution remain high. There are more crime-ridden neighborhoods in the city — as of the day I’m writing this, Englewood is tied for seventh place out of 77 community areas for violent crime over the last 30 days and 19th for property crimes — but the word “Englewood” has become shorthand for South Side crime the way “Chicago” is shorthand for violent cities. The stats don’t bear out either, but the reputation remains.

In 2006, Sam Smith had the opportunity to buy and restore the home on Perry Avenue from a little old grandmother who had lived there with her kids and grandkids for decades.

“After I bought the place and she moved out, I quickly realized that this was the drug and prostitution hub of this whole community. I had to evict the kids and the grandkids out of the house. The son came back two days after the eviction and burned the place up,” Smith said.

The second floor was a total loss, both from the flames and the firefighters’ hoses and axes. The interior would have to be entirely gutted, if he even wanted to keep the place.

“While I was sifting through the ash and trying to assess the damage of the space, one of the neighbors came down to talk to me. One of his questions was ‘Why would you buy in this neighborhood? Don’t you watch the news? There’s nothing out here but guns and drugs and violence.’

“And then he started kind of telling me about the history of Englewood, that it used to be a really thriving place full of businesses and great families. People don’t really communicate with each other over here anymore and he didn’t know what happened. So I went back home and, while I was sleeping, I had a dream that I should, instead of just selling this place, do something with the space that could help to revive Englewood.”

It wasn’t the first time a dream changed Smith’s course. The neighborhood newspaper he started was also spurred by a dream. He had pictured himself laying out pages and making ad sales then, when awake, made it happen. But a dream to revive this block would be harder.

“It was like a movie really, You would drive up and there would be heroin addicts nodding off in the middle of the street, stopping traffic. I had never really seen anything quite like it,” he said.

To do this right, he would have to do this himself. The Gurnee resident would start spending days, weeks at the burnt-out Englewood mansion, turning it into an arts space and becoming a face in the neighborhood.

“So it’s about 1 o’clock in the morning and I’m out welding pieces onto the front door. 1 o’clock in the morning. I turn around to take a sip of water and it’s about 13 young guys standing at the gate absolutely fascinated just watching me,” he said. ”A lot of them were the young drug dealers in the community. They had never really seen anybody who looked like them do anything like I was doing before with this space. It sparked a lot of questions for them.”

“I’m no different than them,” he said. “I probably have a tougher background than they do. And if I can do it, nobody can tell them they can’t.”

Once the arts center was open, Smith started hosting events. Open mic nights emceed by a poet-and-comedian team, open houses, high school reunions. He estimates that about 40 percent of Perry Mansion’s visitors over the years have come from the community, 60 percent from outside Englewood.

He has never had a single incident befall a visitor in eight years the mansion has been open, he said. No one has been robbed, assaulted, harassed, had their car broken into. Nothing, he says.

This isn’t a piece for a newspaper, so I don’t have to feign disinterest. I am biased and partisan here. I like Sam Smith. I want him to succeed and I want you to donate some Christmas charity to his GoFundMe to help him build the Zong.

One of the things I like the most is that this museum in Englewood isn’t utopian. He has foundation funding and is working with local bar groups to fund the Zong. The paperwork certifying his tax-exempt status is orderly. The Perry Mansion Cultural Center started with a dream, but it’s concrete and practical.

The tradesman artist is practical too. It’s art, but not for art’s sake. It’s art for the sake of a community.

“This was creating a safe space that could change the narrative of what this community was,” Smith said.

“What I realized is that most communities that are dilapidated are dilapidated because there is a pervasive narrative that is presented that the neighborhoods should not have anything there, that the people there are bad. And industry doesn’t want to come there. What it does is it draws natural foot traffic out of the areas, so that it is not economically feasible for businesses to come and take advantage of that foot traffic.

“What a space like this does — and what arts programming does period, if it’s strategically placed — it creates a natural flow of foot traffic to an area that would not necessarily have that foot traffic. So it’s a destination point. And when the people who come to the space, they get an opportunity to explore this particular area and see for themselves what the area is, what the people are like, developing relationships with those people.

“But when the people leave, they leave with dollars. they leave hungry, they leave thirsty, they leave looking to explore to see what else the area has to offer.”

See more photos of Perry Mansion

Read about another South Side arts center

See a previous collaboration with the same photographer